Rewriting the Dictionary

James Diggle, Editor-in-Chief of the new Cambridge Greek Lexicon, on 23 years spent overhauling our comprehension of Greek vocabulary

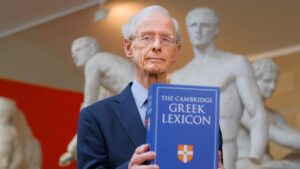

James Diggle displaying the Lexicon in the cast gallery of the Classics Faculty in Cambridge (© Sir Cam)

The Cambridge Greek Lexicon owes its origin, and much of its method, to John Chadwick (1920–98), a pioneer in the study of Linear B with a lifelong interest in lexicography extending from his service on the staff of the Oxford Latin Dictionary (1946–52) to the publication of Lexicographica Graeca: Contributions to the Lexicography of Ancient Greek in 1996. In 1997 he proposed to The Faculty Board of Classics in Cambridge that it should oversee a project to revise the Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon of H. G. Liddell and R. Scott, first published in 1889. Although this lexicon has been continuously in print for over 130 years, and has remained the lexicon most commonly used by students in English schools and universities, it has never been revised, unlike its parent, the original Greek–English Lexicon of 1843, nine times revised, most recently by H. S. Jones (1925–40), and now familiarly known by the acronym LSJ.

It was hoped that the project might be completed within five years by a single editor. So why did it take 23 years and, for some of the duration, occupy five full-time editors?

Before I answer that question, consider how you might go about producing a new dictionary. The most economical way is to base yourself on what has gone before, and then correct and supplement it. That was the method of Liddell and Scott and then of LSJ. The first edition of 1843 was based on a Greek–German dictionary by Franz Passow published in 1831, which itself drew on a similar dictionary published 1805–19. And that is one of the weaknesses of this kind of dictionary-making, and hence a weakness of LSJ. The structure of an article, once fixed, may remain unchanged; old material may be taken on trust and not re-examined; supplementary material is apt to be added piecemeal; translations sometimes live on in English that has become antiquated.

The other way is to start again from scratch: first gather your own material by reading the texts afresh, enter the material on slips of paper, and then put the slips in order. This was the method of Dr Johnson, whose Dictionary of the English Language was the product of his own unaided reading, though he needed six helpers to copy the quotations which he had marked in his books, and it took him eight years. This was the method of the Oxford Latin Dictionary, which employed in all 17 editors, over a period of 35 years. Above all this was the method of the Oxford English Dictionary, which employed an army of volunteer readers and took 70 years.

So, to return to my question, why did the project take 23 years? Because it soon became clear that the plan, as originally conceived, was unworkable. The Intermediate Greek–English Lexicon was antiquated in concept and in detail, and required more than revision. The Faculty Board agreed to widen the scope of the project, and to compile a new and independent lexicon. This would still be of intermediate size and designed primarily to meet the needs of modern students, but it would also be designed to be of interest to scholars, in so far as it would be based upon a fresh reading of the Greek texts, and on principles differing from those of LSJ. Reading of the texts afresh would not have been feasible without the aid of computer technology. The online searchable Thesaurus Linguae Graecae made it possible, for the first time in the history of lexicography, to find every occurrence of every word at the press of a computer key, and to examine that word in its context, often with an accompanying translation.

The coverage of the Lexicon extends from Homer to the early second century AD (ending with Plutarch’s Lives). We include all of the major authors who fall within that period, and most of the minor ones, and many new texts unknown to LSJ, such as Sappho and Menander, texts which have turned up on papyri in recent years. About 90 authors are covered, and there are 38,798 headwords. There are also over 7,500 cross-references. For example, no fewer than 115 different forms (regular or dialectal) of the verb εἰμί, I am, are not only listed under the headword but also cross-referenced in their alphabetical place.

Here are some of the Lexicon's distinctive features, several of which I shall illustrate later:

- We do not organise entries according to chronological or grammatical criteria, as LSJ normally does. In other words, we don't automatically start with Homer, or with the active voice before getting to the middle or passive, or put constructions with the accusative before constructions with the genitive or dative. We organise entries according to meaning. We aim to show the developing senses of words and the relationships between those senses. So, we begin with the root sense of a word, which may well appear not in the earliest author who uses that word, but in a later author. And then, in numbered sections, we trace its applications in the different contexts in which it appears.

- For some longer entries (especially verbs) we give an introductory summary to show the reasoning behind the grouping or sequence of sections. As an example of this, take the verb ἔχω, one of the commonest Greek verbs, whose basic senses are 'have' and 'hold'. Our entry for this verb occupies three and a half columns and runs to 55 sections. If a verb has as many applications as this, you need to provide the reader with signposts, to show how you have organised the material. So, in our summary of the groups, we move from the physical, sections 1–3 ('hold by physical contact'), to the less physical (section 4 'hold in one's possession'), then to the non-physical (beginning in section 15), as for example in 'have thoughts' or 'have consequences', and this development is marked by a shift of sense from 'hold' to 'have’. There is also a distinct group (from section 29 onwards) in which the sense is 'hold back, constrain or restrain'. And finally, there is a group of intransitive uses, and a group of uses in the middle voice. This introductory summary makes it easier for the reader to navigate through what is a very long and complex article. If you compare our treatment with that of LSJ, you will find there several columns of densely packed material, with little to guide you through it. The labyrinth of Minos was more easily penetrable than many an article of LSJ.

- Where necessary, we give explanatory definitional phrases, in addition to translations. What is the difference between a definition and a translation? A definition describes the general sense of a word, and it may be applicable to that word in a variety of contexts. A translation reflects the meaning of the word in a specific context. On the page we make a visual distinction between these two by giving the definition in Roman font, the translation in bold.

- We don't give precise references to specific passages (like Euripides, Medea 245), but use author abbreviations alone (for Euripides, for example, simply capital E.), and, for the most part, we don't give Greek quotations. The omission of such citations and quotations allows room for the inclusion of a great deal of additional material, in particular for fuller description of meanings and for illustration of usage in a wider range of passages. If you cite a single specific passage, without translating it, as LSJ often does, you are doing no favours to the learner, and you run the risk, by being so selective, of giving a partial or distorted picture. Whenever we do give a Greek quotation, we translate it.

- We use contemporary English. We don't call βλαύτη (like the Intermediate Lexicon) 'a kind of slipper worn by fops', nor do we translate κροκωτός (like LSJ) as 'a saffron-coloured robe worn by gay women'. And what of the words which brought a blush to Victorian cheeks? LSJ could have claimed, in the words of Edward Gibbon, 'My English is chaste, and all licentious passages are left in the obscurity of a learned language'. We spare no blushes: we don't translate the verb χέζω as 'ease oneself, do one's need'. We define it as 'to defecate' and translate it as 'to shit'. Nor do we explain βινέω as 'inire, coire, of illicit intercourse', but simply translate it by the f-word.

Here is an example, which illustrates our use of definitional phrases and the way we trace developing senses, as well as some distinctive typographical features. I have chosen a familiar word, the adjective καλός. Before we get to the meanings, we give a small amount of information relating to dialect, spelling and vowel length. Then, in section 1, we offer a definition (in Roman font), 'beautiful in appearance'. This is the root sense of the adjective, the sense from which all others are derived. We list the subjects to which the adjective in this sense is applied: '(of men, women, deities, animals, their bodies, parts of the body)'. Three translation words are offered (in bold font), not just 'beautiful' but also 'handsome' and 'good-looking'. This use is so common that a bare Hom. + is all we need. Then in section 2 we bring in a different type of noun: '(of places, features of the natural world)'. The original definition is still applicable, but not all of the original translations will suit, so we bring in a different one, 'fair'. Then, in section 3, we move from natural things to created things: '(of created things, such as clothes, weapons, buildings)', with the translations 'beautiful, handsome, fine'. In section 4 we move away from beauty of appearance to beauty of sound: '(of a voice, singing, or similar)', for which the single translation 'beautiful' suffices. Then we move away from beauty altogether, to a more general sense, for which the rather elaborate explanatory definition reads '(as a term of general commendation, of things or circumstances, good in terms of quality, practical usefulness or capacity to satisfy or give pleasure)', and here we offer the translations 'good, excellent, fine', and for the first time we introduce a new author label, as an ironical use appears, from the tragic poets onward. Then in section 6 some applications of this sense in specific circumstances. Then (in 7–8) some uses of the neuter in verbal or prepositional or phrases. And in these sections our translations are now in italic: this is because we are translating a phrase, not a single word. Then in 9 we move to something decidedly new, when the adjective acquires a moral connotation, in application to things said or done. And in 10 we have a specific development of this use, when it is paired with ἀγαθός, 'good', but not before Herodotus, to describe a particular type of man, occasionally woman, who combines various types of excellence, 'fine and good, upstanding, decent', and this pairing becomes so much a part of ordinary usage that it can even be applied to places or manufactured items—an island, an oil flask.

Samuel Johnson described the lexicographer as 'a harmless drudge'. And Housman mocked the compilers of the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae as 'the chain-gangs working at the dictionary in the ergastulum at Munich'. Well, we've drudged and we've slaved. But we have, I hope, created a work which will be of service to students, and more than students, for a good few years, and will not disappoint those many individuals and institutions who, by their generosity, sustained the project through those long years. Among those to whom we are indebted is the Hellenic Society. To mark our gratitude we have presented to the Society a specially commissioned de luxe copy, bound in leather.

The Cambridge Greek Lexicon, edited by J. Diggle (Editor-in-Chief), B. L. Fraser, P. James, O. B. Simkin, A. A. Thompson, S. J. Westripp, is published by Cambridge University Press, 2021, in two volumes, £64.99, pp. xxiv, 1529.