Crucible of Europe

Judith Herrin charts the fascinating development of Ravenna, ‘centre of connectivity par excellence’

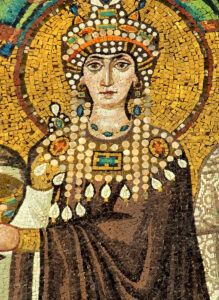

Theodora, detail of a mosaic at Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna (Credit: Petar Milošević/CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons)

In AD 402, when Ravenna was chosen to be the new imperial capital of the western half of the Roman Empire, few contemporaries would have anticipated its later dominance in the West. Yet the decision taken by the young Emperor Honorius, when his court in Milan was under severe pressure from Alaric the Goth, proved to be an inspired strategic redeployment. Upon the advice of his leading general, Stilicho, Honorius moved his court and the entire imperial administration to Ravenna, famous for its enormous harbour at Classis. While the harbour silted up gradually, Ravenna expanded, transforming itself into the leading western metropolis with magnificent buildings decorated in brilliant mosaics.

The settlement at Ravenna was originally built on sandbanks and wooden piles with bridges over the many canals that flowed around and into the city, just like Venice in later centuries. It became a Roman city with municipal buildings, facilities for public entertainment, temples and eventually churches scattered across marshy land separating the numerous tributaries of the Po. Once the enormous apparatus of government was established in its new centre, Ravenna developed into a nigh-impregnable fortress, often besieged but rarely captured by force. Galla Placidia, empress-mother, who lived there from 425-50, Bishop Neon (c. 451-73), re-builder of the Orthodox Baptistery, Theoderic the Goth (493-526) and Bishops Ecclesius, Victor and Maximian, in the first half of the sixth century, were the leading patrons, and some of their churches with glowing mosaic interiors survive, though their palaces do not.

Through the sixth and seventh centuries Ravenna extended its metropolitan role under the aegis of Constantinople, now the capital of the Roman Empire. Constantine I’s inauguration in 330 of the city, also known as New Rome, continued to dominate the Mediterranean world, providing guidance in legal matters, diplomatic disputes, political negotiations and theological problems. Although many of the ‘barbarian’ rulers and bishops in the post-Roman world disputed its influence, Constantinople exercised a hegemonic leadership in these centuries. This is something that many Europeans familiar with the Roman classical heritage ignore. Rome’s greatest achievement was the creation of this megalopolis, Constantinople, now Istanbul, which sustained the one Roman world now indisputably centred on the Bosporos. It defeated the Persians and defied Islam.

From 540 to 751 Ravenna constituted its most important western base, selected as the seat of an exarch who ruled over Italy. In this way Ravenna was elevated to a determining role: it served as the entry point for East Mediterranean imports, judicial and theological rulings, military and diplomatic contacts, artistic innovations and all manner of influences that found their way over the Alps into northern Europe. It attracted a very mixed population of Syrian merchants, Jewish communities, Roman senatorial families and local Italian craftsmen, who maintained their own languages visible in documents witnessed in Greek, Latin and Gothic that were deposited in the municipal archive.

Above all, it had a special allegiance to the Goths. The mixture of cultures which is so characteristic of European cities stemmed from the reign of King Theoderic, who had been sent as a child hostage to the Byzantine court and was formed by its perspectives. In Constantinople he learnt how to rule an empire: to mint a reliable currency and collect taxation in it; to record every legal decision in triplicate; to arrange imposing court rituals, and to promote military skills, medical expertise, diplomatic practices and intellectual achievement. After a decade of education in these imperial traditions, which Constantinople hoped would make him a reliable ally, Theoderic was sent back to his Gothic people and immediately asserted his independence, until eventually he was given imperial permission to take his people to the West.

Once established in Ravenna he built a mini-Constantinople there, integrating ‘barbarian’ and ‘Roman’ elements in a decisive new synthesis. Partly because his Gothic supporters always constituted an Arian Christian minority, Theoderic also insisted on the toleration of religious difference, imposing a principle that was much quoted by sixteenth-century Protestant reformers. His incorporation of imperial methods of government set Ravenna on its leading role in European development.

In addition to this political promotion, Ravenna had an intrinsically important location that made it a centre of connectivity par excellence. With access via the Po valley up to Pavia and Milan, trans-Apennine routes to Rome and western Italy, and maritime communication with all the lands bordering the Adriatic, Ravenna was particularly well placed to link the two halves of the Mediterranean world. The tremendous forces that divided that world and would forge a new settlement in its European region were enabled, focussed and in part defined by it. Ravenna’s history, therefore, is not simply an account of the city, its rulers and its inhabitants’ way of life, but also draws on the far-flung powers attracted to and through it, that made Ravenna a crucible of Europe.

A vital stage in this development is marked by the depictions of Justinian and Theodora, two of the most famous mosaics in Ravenna, in the church of San Vitale, dedicated in 547. They encapsulate a majestic power marked by the regalia and clothing of the imperial rulers, who never went to Ravenna but dominated the Mediterranean world in the sixth century. Throughout the medieval period these mosaics elicited changing reactions. Charlemagne, who visited Ravenna three times, and his German successors in the second half of the tenth century, Otto I, Otto II and especially Otto III, contemplated their significance in novel political circumstances. The imperial portraits reflect the continuous influence of the wealth, culture and direct role of Constantinople itself in Ravenna, a city that not only nurtured expertise in Greek, but also preserved a curiosity about the physical world, mountains and rivers, as well as imperial geography.

This facet of Ravenna’s history is documented by the anonymous scholar who wrote a Cosmographia that ‘explored the whole world’ from his vantage point in nobilissima Ravenna, which he placed at the centre of the Mediterranean. His combination of Gothic, Latin, Greek and Christian elements created a fulcrum of early medieval culture informed by a high esteem for classical learning. Another stage in the process may be illustrated by the mosaic erected in Sant’Apollinare in Classe in the late seventh century to mark the moment when the church of Ravenna became independent of papal control. In the long-running rivalry between Ravenna and Rome, this was to prove a short-lived period of freedom but Archbishop Reparatus ensured that it would never be forgotten by his commission of a new mosaic.

When Charlemagne removed marble columns and other building material to construct his new capital at Aachen, he also took with him the great statue of a mounted emperor that Theoderic had adapted to represent himself. The Gothic king had erected it in front of his palace in Ravenna, in imitation of Justinian’s equestrian statue on top of a column in central Constantinople. Theoderic was also an invader reshaping the legacy of Rome, with whom the newly crowned Frankish emperor could identify. Charlemagne has traditionally been hailed, in Alcuin’s phrase, as the ‘father of Europe’, as if he acted alone. But the foundations of western Christendom that he exemplified were laid in Ravenna, whose rulers, exarchs and bishops, scholars, doctors, lawyers, mosaicists and traders, Roman and Goth, later Greek and Lombard, forged the first European city.