Ancients in the New World

Germán Campos Muñoz explains why the reception of classical ideas in South America has always been deeper than meets the eye

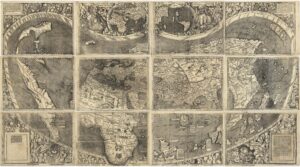

Ptolemy faces Vespucci in the second and third top panels of this 1507 map by Martin Waldseemüller made in France. This is the earliest map in history to feature the word “America”. (© Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division)

It has been two years since I published The Classics in South America (Bloomsbury, 2021), in which I examined five cases of classical reception in South America, from the colonial period through to the present day. The authors discussed in the book are heterogeneous. They include an Aristotelian Jesuit who came to be hailed as the Pliny of the New World; a Mestizo historian who identified his native city of Cuzco, capital of the Inca Empire, with ancient Rome; a Peruvian epic poet who crafted an artificial language by mixing Spanish and Latin; an illustrator who strategically decorated plans for Lima’s defensive walls with passages from Virgil’s Aeneid; a group of conspirators who used the fabled assassination of Julius Caesar as a template for their attempt against Simón Bolívar’s life; and 20th-century musicians and filmmakers who turned the myth of Orpheus into a quintessential Brazilian motif.

This variety of cases alone gives an idea of the wide range of cultural practices in South America that can be examined through a classical lens.

The relationship between Classics and the Americas may be crystallized in the term mundus novus or “New World.” This story begins early, with Amerigo Vespucci, the 15th-century Florentine merchant and navigator whose name inspired the toponym America. Much is in doubt about his character (particularly the veracity of his exploratory claims), yet his name became entangled with the history of the Americas because he was the first, or so it seems, to identify that landmass as the “New World.”

‘These [lands],’ says Vespucci to his patron Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici in a famous letter written around 1503, ‘we may rightfully call a new world (...). For this transcends the view held by our ancients, inasmuch as most of them hold that there is no continent to the south beyond the equator, but only the sea which they named the Atlantic.’ The letter would soon reach press and circulate widely across Europe, especially in its Latin version.

This passage reveals how the classical world was implicated in the conception of the New World from the outset. As Vespucci intimates, the issue with “those lands” (by which he meant the few areas of South America and the Caribbean that had been explored up to that point) was not just that they were “new” to early modern Europeans. The real problem – the real newness – was that such a colossal mass of land was nowhere to be found in the hefty treatises penned by Herodotus, Aristotle, Strabo, Ptolemy, Pliny, or any of those Vespucci calls “our ancients.”

Furthermore, the sole existence of that continental landmass overrode classical pronouncements that had declared the southern hemisphere uninhabitable. That was the crux of the matter: the New World was new primarily because the ancient Greeks and Romans knew nothing about it. It did not matter to Vespucci that what he called the New World was not new at all to its Indigenous inhabitants; for good or bad (perhaps mostly for bad), the label stuck and quickly became a defining image of the Americas.

One might suppose that, once an entire “world” was defined as new by virtue of evading the notice of classical authorities, the classics themselves could have been considered irrelevant. What happened was the exact opposite. For some, the advent of the New World was taken as evidence of a modern triumph with respect to the boundaries of ancient knowledge and power.

This meant that classical motifs could be invoked precisely to prove their limits. Consider the famous case of the pillars of Hercules. A mythical tradition reported by Pindar and other ancient writers claimed that Hercules had installed two pillars at the westernmost edge of the earth (later assumed to be the Strait of Gibraltar) to mark the limits of the oikoumene or inhabitable world. By the early 16th century, the motif had made its way onto the royal emblems of Charles V, Hercules’ fabled columns decorated with the phrase plus ultra (interpreted as “further beyond”).

While scholars debate whether Charles himself consciously sought to allude to the ancient myth with that phrase, the claim would eventually be made that plus ultra was an inversion of the ancient injunction non plus ultra or “not further beyond,” attributed to Hercules, and that the amended plus ultra implied breaking those classical boundaries. Reaching the New World meant, in this way, superseding limits that ancient explorers, sages and heroes considered universal. It made perfect sense to convey Charles’s imperial eureka by inscribing the classical pillars and the defiant plus ultra on the highest symbols of the realm.

But this sense of euphoria would be only one of a number of outcomes. Many others resisted the notion that the New World had been altogether ignored by classical authors, postulating that, if the ancients did not possess a fully developed sense of the New World, they nevertheless surmised it. Columbus himself inadvertently began this approach. Even if he didn’t think of what he called the “Indies” as a New World, he saw in this fragment of Seneca’s Medea a clear prediction of his own voyages:

‘The time will come / in a number of years, when Oceanus / will unfasten the bounds, and a huge / land will stretch out, and Typhis the pilot / will discover new worlds, so / the remotest land will no longer be Thule” (from Columbus’s Book of Prophecies, translated into English by Delno C. West and August Kling).

Decades later, when the notion of “New World'' was universally accepted, his son Ferdinand Columbus would proudly scribble, in the margins of his own copy of Seneca’s Medea, this annotation: ‘This prophecy was fulfilled by my father the Admiral Christopher Columbus in the year 1492.’

An array of colonial authors would also rush to identify the Platonic Atlantis with the New World (the same was done with Ophir, Thule and other legendary outposts of the ancient imagination).

The whole corpus of classical texts thus became fair game for intellectuals trying to find hidden references to the New World.

While obscure authors proved especially useful, the most renowned among the classics were not exempted. Thus the German philologist Eramus Schmidt (1570–1637), who endorsed the Atlantis theory, claimed that Homer foresaw “our America” when referring to the western Ethiopians who lived where the sun “plunged” (Odyssey 1.22–4) and that Virgil did the same when Anchises, as part of his prophecy, claimed that Augustus would extend his empire to the land beyond the stars (Aeneid 6.795–6).

Others recognised a unique opportunity to fulfil the role occupied by classical authors in antiquity – to become, so to speak, New World classics. The transition from the late 16th to the early 17th century provides multiple instances of this drive. The bookseller Diego Mexía de Fernangil, translator of Ovid’s Heroides, fancied himself a modern Ovid exiled in a barbaric New World reminiscent of the ancient Pontus; Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, the great Mestizo historian of the Inca Empire, wished to become a new Julius Caesar, equally famed for his military lineage and historiographic talent; and the Jesuit José de Acosta, author of a treatise suggestively titled Natural and Moral History of the Indies, came to be hailed as the “Pliny of the New World.”

In the introduction to Origin of the Indians of the New World (1608), the Dominican Gregorio García would synthesize this idea of New World reincarnations of the classics by reminiscing about the trips of Pythagoras to Memphis and Plato to Egypt. He compared the Greek philosophers to the European scholars who came to the New World and who, ‘though wise in matters of the Old World, were ignorant in those of that other Orb.’ By tendentiously imagining the New World as a blank slate, an array of authors actively sought to take the opportunity to become classics for the generations to come.

Conversely, the newness of the New World also produced anxieties for many colonial writers. A sharp example is that of the intellectual class of Lima, capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru. As this city became one of the main political and economic centres of the Americas in the 17th century, its power and wealth seemed to be at odds with its “short” history: Lima, founded just about in 1535, lacked the prestigious antiquity associated with the great urban centers of Europe.

The opening of Bernabé Cobo’s History of the Foundation of Lima (1639) symptomatizes this concern: ‘The city of Lima is head and court of this kingdom of New Castile in Peru, and is so illustrious in its main excellences, that it is only lacking in years to be able to compete with the greatness and majesty of the noblest cities of Europe.’

About a century later, the Limenian polymath Pedro de Peralta Barnuevo attempted to compensate for this ‘lack of years’ in The Founding of Lima (1732), a ten-canto heroic poem about the deeds of conquistador Francisco Pizarro that led to the foundation of Lima in 1535. Rehearsing the trope of Anchises’ prophecy (mandatory for epic poems following the model of the Aeneid), Peralta makes a young spirit appear to Pizarro to announce the political, social and architectural future of Lima, but in so much detail that the garrulous prophecy takes up almost half of the epic poem!

In sum, the newness of the New World, inaugurated by Vespucci, sparked a long history of mixed claims. There were hurrahs about the moderns’ triumph over the ancients, beliefs about the prophetic powers of the classics and their cryptic references to the Americas, demands for “new” classics to populate the “New” World, and anxious attempts to compensate for the “short” history of the Western hemisphere.

All these reactions confirm what classical reception studies in the Americas repeatedly show: that the use of Greco-Roman classics in South America was never a matter of passive consumption of a prestigious tradition, or the derivative implementation of European paradigms of education in territories occupied by colonial powers. Far from that, the phenomenon of classical reception in the New World was part and parcel of the ideological and intellectual mindset that led to the exploration, invasion and colonization of the Americas; to the violent conflicts and heated debates that defined its independence campaigns and republican projects; and to the series of social and political movements that continue to characterize its complex modernity.