From Aristotle to Xunzi

Jingyi Jenny Zhao asks whether Aristotle and the Chinese philosopher Xunzi had more in common that meets the eye

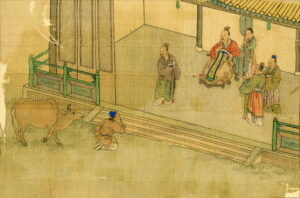

Xunzi is considered the third greatest Confucian after Confucius and Mencius, whose lives are represented in this album leaf. Ink and colours on silk. 1644-1911 (© Trustees of the British Museum)

A contrast is often drawn between the ancient Greeks and the Chinese: Greek philosophy was deeply concerned with reason and rationality, while Chinese philosophers considered morality to be of prime importance. But does the contrast hold when we look at the role rationality and morality played in Greek and Chinese thought about human nature and potential? I focus here on two philosophers – Aristotle and Xunzi.

Aristotle (4th century BC) and Xunzi 荀子 (3rd century BC) both lived in periods that preceded the unification of their worlds – the conquest of the Greek states by Alexander the Great, and the unification of China by the Qin emperor in 221 BC. Xunzi, to whom the Xunzi text is attributed, is generally held to be the third greatest ‘Confucian’ after Confucius and Mencius. Unlike the aphoristic Confucian Analects and the Mencius, which is largely in dialogue form, the Xunzi is written primarily in the form of a treatise and contains extended arguments on topics ranging from ethical cultivation, ritual, politics and government, to tian, Heaven.

Despite the fact that Aristotle and Xunzi lived in societies that differed socially and politically – societies, indeed, that were not in contact with each other – several aspects of their philosophy are strikingly similar. One particularly interesting point of commonality to note is that both set out a scala naturae, whereby humans are clearly distinguished from other things; human beings’ unique capacities are then used as a basis for discussions about ethical cultivation and the fulfilment of their potential.

For Aristotle, plants possess the nutritive faculty only, while animals have sense perception and therefore also the appetitive faculty (this includes epithumia, an appetite for what is pleasant). In addition to having the nutritive and sensory faculties, humans and anything else which is similar or superior (by which Aristotle means god) have thought (to dianoētikon) and intellect (nous), which make them more complex than plants and animals and entail that they have a different function in life. Aristotle also stresses that, if we were to speak of a human being qua human being, we ought to neglect the parts of the soul that are not distinctive to humans but look to the power of reasoning (logismos). For Aristotle, leading a life of eudaimonia or flourishing involves ‘the activity of the rational part of the soul in accordance with the virtues’, where eudaimonia is restricted to humans.

What, then, about Xunzi? In a well-known passage, we are given the following account:

Water and fire have qi but are without life (sheng 生). Grasses and trees have life but are without awareness (zhi 知). Birds and beasts have awareness but are without a sense of propriety (yi 義). Humans have qi, life, awareness, as well as a sense of propriety, thus they are the noblest under heaven. (HYXY 28/9/69-29/9/70) (all translations of the Xunzi cited are based on Hutton with modifications)

While Aristotle identifies the rational capacity of human beings as the characteristic that distinguishes them from animals, for Xunzi, humans are unique from other species because of yi, their sense of propriety, otherwise translated as ‘the capacity to behave correctly’, ‘the sense of justice’, or quite simply, ‘morality’.

Joseph Needham, the prominent Cambridge biochemist and historian of science, compares the scala naturae in Aristotle and Xunzi in vol. 2 of Science and Civilisation in China. He observes: ‘It is typical of Chinese thought that what particularly characterised man should have been expressed as the sense of justice rather than the power of reasoning’ (1956, p. 23). Following Roel Sterckx (2002, p.89), who has criticised Needham for pitching morality against reason, let me discuss further why it might be problematic to characterise the Chinese and Greek conceptions of humans in such terms, even if the two philosophers do on the surface appear to be flagging up different qualities that they believe to be specific to humans.

The fundamental issue with pitching rationality against morality, it seems, is that it overlooks the fact that the rational and the moral are often closely intertwined in ancient and contemporary ethical discourse, so much so that rationality in the context of ethics often implicates acting morally, and acting morally often involves undertaking rational calculations so that the actions accord with some kind of reason or principle. The relationship between morality and rationality is of course a question that has had a long history and is still the subject of an ongoing debate; Immanuel Kant, for example, has famously argued that the supreme principle of morality is a standard of rationality – the ‘categorical imperative’. Without getting distracted by later debates, let me raise the question, what does ‘rationality’, more specifically, ‘acting rationally’, mean for the Chinese philosophers, in the present case, Xunzi? And what parallels can we draw between Xunzi and Aristotle in this respect?

In the Xunzi, cultivation is frequently discussed in terms of learning to prioritise a sense of propriety over the desire for personal benefit or profit (li 利). It is said that all humans by nature have a liking for food and drink, goods, and profit – but one gradually learns to refrain from merely following one’s primal instincts, and instead to adjudicate between different choices and act upon something that accords with ritual and a sense of propriety. How does one do that? Well, even though humans are defined by their sense of propriety, that moral sense needs to be cultivated (unlike plants and animals, for whom there is no cultivation of capacities involved). For Xunzi, the heart-mind (xin 心), which has both cognitive and emotive functions, plays a vital role in cultivation and rational decision-making. An important part of cultivation involves receiving teachings and following ritual practices so that one gets accustomed to responding appropriately to desires using the heart-mind. It is not the case that through cultivation, one learns to have fewer desires; rather, the heart-mind deliberates whether a desire should be fulfilled, leading the body to put it into action, which reflects ‘conscious exertion’ or ‘artifice’, wei (偽) (contrasted with one’s inborn nature, xing 性). See, for example, this passage:

Thus, when the desire is excessive but the action does not match it, this is because the heart-mind prevents it. If what the heart-mind approves of conforms to the proper patterns (li 理), then even if the desires are many, what harm would they be to good order? When the desire is lacking but the action surpasses it, this is because the heart-mind compels it. If what the heart-mind approves of misses the proper patterns, then even if the desires are few, how would it stop short of chaos? Thus, order and disorder reside in what the heart-mind approves of, they are not present in the desires from one’s dispositions. (HYXY 85/22/60-2)

In other words, the correct functioning of the heart-mind allows the agent to act upon a certain degree of reflection and rational calculation rather than the primal responses and selfish tendencies that humans have by birth. In so doing, one exercises a sense of propriety that is in accordance with what is taught. So the very choosing of propriety over personal profit, something that goes against humans’ inborn tendencies, indicates that rational thinking or reflection is involved.

How is it that humans, alone of animals, are capable of leading lives that accord with a sense of propriety? Xunzi explains that it is because they alone are capable of making distinctions. He uses the concepts fen 分 (divisions) and bian 辨 (discriminations) to cover the making of social divisions, the recognition of one’s place in society, and the distinction of right from wrong. We can argue that these are rational processes which involve making discriminations between values, and that provides the basis for cultivating a sense of propriety.

As I hope to have shown in this brief account, even though Xunzi can be contrasted with Aristotle in how the human is defined, whereby we find Xunzi highlighting humans’ sense of propriety and Aristotle their reasoning capacity, what we are confronted with is not a direct contrast – indeed, there is much that holds the two philosophers in common. For Xunzi, possessing a sense of propriety in fact entails reasoning about what might be the best courses of action to take; for Aristotle, by virtue of having the reasoning capacity, human beings are equipped with the ability to make moral choices, exercising both intellectual and practical virtues. Good purposive choice (prohairesis spoudaia), it is said, requires the reasoning to be true and the desire to be right, so that the two parts of the soul, the rational and the non-rational, are in harmony with each other (animals do not have purposive choice, and cannot be virtuous in the strict sense). As Aristotle says in the Nicomachean Ethics, ‘the purpose of our examination is not to know what virtue is, but to become good, since otherwise the inquiry would be of no benefit to us’ (all translations of Aristotle cited based on Broadie).

Ultimately, for both Xunzi and Aristotle, the moral and the rational are closely intertwined: being moral would imply being rational, and humans, alone from animals, are rational beings who are capable of leading moral lives, provided that they succeed in ethical cultivation. However, the difference between the two is that for Xunzi, ‘rationality’ is couched in the terms of ‘a sense of propriety’ or ‘morality’, while for Aristotle, it is the other way round – humans are first and foremost defined by their reasoning capacity, which is the faculty that grants them the capacity to be moral.

In reading Aristotle and Xunzi, one cannot fail to notice the emphasis placed on the importance of ethical cultivation in the fulfilment of human potential. In conceptualising the process of moral training and the overcoming of certain inborn tendencies, both philosophers choose to employ the metaphor of the warped wood:

And we should consider the things that we ourselves, too, are more readily drawn towards, for different people have different natural inclinations; and this is something we shall be able to recognise from the pleasure and the pain that things bring about in us. We should drag ourselves away in the contrary direction; for by pulling far away from error we shall arrive at the intermediate point, in the way people do when they are straightening out warped pieces of wood. (EN 1109b1-7)

Thus, warped wood must await steaming and straightening on the shaping frame, and only then does it become straight. (HYXY 87/23/5)

Likewise, when wood comes under the ink-line, it becomes straight, and when metal is brought to the whetstone, it becomes sharp. The gentleman learns broadly and examines himself thrice daily, and then his knowledge is clear and his conduct is without fault. (HYXY 1/1/2-3)

What are we to make of these analogies, juxtaposed in such a way? A piece of wood which is naturally warped is capable of being straightened; however, it is of utmost importance to recognise what might be effective in correcting the wood and making it straight. Xunzi, known for his claim that human nature is bad (xing e 性惡), warns people that without education, one cannot realise one’s potential to act in accordance with a sense of propriety and become the ‘noblest under heaven’. Aristotle, on the other hand, does not pursue the topic of human nature by labelling it as ‘good’ or ‘bad’; rather, he says that ‘the excellences develop in us neither by nature nor contrary to nature’, that we are naturally able to receive them, and that habituation plays a key role in developing the excellences.

Furthermore, learning to be pleased by what is truly pleasant and pained by what is truly painful constitutes an important step in moral cultivation. In this way, for both Xunzi and Aristotle, education and the accumulation of good practices are essential if we are to develop into human beings in the fullest sense.

Returning now to the topic of rationality, we can say that in the early Chinese philosophical tradition, there is no direct equivalent of the Greek idea of logos, which has a very wide semantic range. Indeed there is no one word that would correspond directly to ‘rational’ or ‘rationality’ in the Chinese corpus. But that is not to say that the idea of rationality does not figure in Chinese philosophy, or that the Chinese philosophers did not consider it important for humans to possess the capacity for rational decision-making. As I hope to have shown, taking a comparative approach can often reveal interesting insights into fundamental – and often difficult – concepts such as ‘rationality’, in terms of what this idea signifies in different contexts, and how it translates into the philosophical language of different cultural traditions. Comparing the Chinese tradition with the Greek, and more specifically in this case Xunzi with Aristotle, alerts us to the fact that one often has to look beneath the surface of certain claims to uncover what is shared and what is distinctive about two philosophers, or philosophical traditions.

Further reading

Hutton, Eric. Xunzi: The Complete Text. Translated with an Introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014.

Lloyd, G. E. R. The Ambivalences of Rationality: Ancient and Modern Cross-Cultural Explorations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Lloyd, G. E. R., and Jingyi Jenny Zhao, eds. Ancient Greece and China Compared. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Sterckx, Roel. The Animal and the Daemon in Early China. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002.