The Perks of Growing Old

John Davie says that ageing wasn’t always the hurdle it appeared in ancient Greece

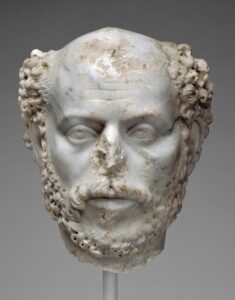

Growing old gracefully: a portrait head of a balding man by an unknown artist, c. AD 240, Asia Minor (Image courtesy of the Getty Open Content Program).

Old age in English literature generally gets a bad press. Think of Jacques’ bleak portrait in his Seven Ages of Man speech:

Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

This comes, of course, from As You Like It, but is hardly as we would like it.

For the Ancient Greeks the problem was compounded by their love of physical beauty and corresponding distaste for old age. Priam, the elderly king of Troy, in trying to persuade his son Hector not to fight Achilles makes a telling comparison:

In a young man killed in war everything looks well, though he lies there torn by the sharp bronze – dead he may be but nothing revealed of him lacks beauty. But when an old man has been killed and the dogs are savaging his grey head and grey beard and private parts, there is no sight more pitiful for wretched mankind to witness.

Underlying this is the Greek horror of ugliness, of the physical decay that they saw as an inevitable part of growing old. It is significant that the Greek adjective kalos can mean both “honourable” and “beautiful”; likewise its opposite, aischros, can mean “ugly” as well as “dishonourable”. This is reflected politically by the word “aristocracy”, literally “the rule of the best”, who were invariably of noble birth and usually of fine appearance. “Like the gods” is a common description of princes and kings in Homer and refers to their appearance, not their character. Hephaestus is mocked on Olympus as he hobbles up and down serving wine to the other gods and goddesses. Homer here anticipates the unpleasant world of Verdi’s Rigoletto.

In the Odyssey, part of the reason why Odysseus meets such contempt from the Suitors is that he is disguised as an old beggar, while they are young men in their prime. A glimmer of a more enlightened attitude to come appears in the character of the swineherd Eumaeus, who is old and dirty but has an inner nobility that belies his humble origins.

This aristocratic outlook never really left the Greeks. We might suppose that old age would not diminish a king’s authority, but Achilles worries about his old father at home losing precisely this.

Sparta was, famously, a warrior society that based its success on military training and excellence, that is, on people of fighting age, not the elderly. But it was in Sparta that real political power was held by elders, the so-called gerousia, a council of 28 men over 60 years of age, chosen for their moral worth. They had the power to veto proceedings in the assembly of the people if they felt a bad decision had been taken, a state of affairs much admired by Plato in democratic Athens. However, these senior councillors wielding such power in Sparta were elected by the people but not from the people, and so the principle of aristocratic superiority held firm.

How were the old regarded in classical Athens? On the positive side, we know that within the family the status of elderly parents was high, as in modern Greece and Italy. The Greek word tropheia illustrates this. Originally used of the wages paid to a nurse, the word was also used metaphorically to describe the debt owed by children to the parents who had reared them, and grandparents were expected to receive honour from their family. There was certainly no question of putting them in a home.

When death came, mourning lasted for 30 days after burial. Family members were expected to visit the tomb on the third, ninth and thirtieth day. After this special month, the grave was visited every year on the anniversary of death, with ribbons and wreaths of flowers, and food and drink offerings over the grave. All this implies respect for the elderly but it is also true that the Greeks feared haunting or ill omen if they neglected the dead, and honouring them properly was seen as an act of worship that was vital to both image and reputation.

Tragedy and comedy were performed in the theatre of Dionysus throughout the 5th century BC, and in many ways functioned as further education for the citizen body. Old age receives mixed reviews from the dramatists.

In his Agamemnon, the first play of his Oresteian trilogy, Aeschylus shows a chorus of elderly men condescending to the queen, Clytemnestra, as a foolish woman, while she runs rings round them and proceeds, unhindered, to murder her husband on his return. “It is always springtime for an old man to learn a lesson”, they sing, but Aeschylus shows them to be locked in a mental winter by their lack of wisdom.

Euripides in his play Alcestis presents us with a strange situation: a young king is fated to die but his wife insists that she will die in his place. At her funeral the king blames his old father for not giving his life for his son’s. His words are full of bitterness:

How insincere they are, these prayers for death voiced by the elderly, these complaints they make against old age and the tedious passing of the years! If death draws near, not one of them wants to die; old age is suddenly a burden that weighs lightly on their shoulders.

The king’s father will have none of this. “You are happy to see the sun’s light,” he tells his son. “Do you imagine your father is not? It’s a long time I reckon I’ll be spending dead, a long time, and only a short one alive, but all the more precious for that.”

In his Bacchae Euripides gives an insight into the frustration the old can produce in the young, a sentiment that many in the audience may have shared: “How churlish a thing in men is old age, with its scowling face!”

And in Euripides’ The Children of Heracles, the great hero is dead and his children are being persecuted. Iolaus, an old man now and Heracles’ loyal friend, wishes to fight in a battle to decide the children’s fate, despite his advanced years. Nothing will deter him and by a miracle he is transformed from an old man to a young one who turns the tide of battle. The point is clear: old age denies men the power to back up their intentions.

Comedy in classical Athens, like comedy in all ages, involved distortion and exaggeration but, in order to be genuinely funny, it had to portray life in a recognisable way to its audience. Old men are regular characters in the plays of Aristophanes and usually represented as gullible and not as clever as they think.

In his early play, Knights, Demos, the people of Athens, is an old man led by the nose by unscrupulous politicians. In the later Clouds, old Strepsiades enrols his wastrel son in the school of Socrates, hoping he will become a clever fellow capable of winning any argument. The son learns so well that he ends up having no respect for convention or tradition but follows his natural instincts instead, which means he beats up his irritating old father, who learns a painful lesson. In a later play, Frogs, those who do violence to their parents are consigned to the depths of Hades and this is far more in line with normal Athenian thinking. Old women are treated no more kindly in the Lysistrata, where the women of Athens decide to go on a sex-strike to persuade their husbands to stop fighting the war against Sparta. Three old women are portrayed as desperate to get a young man into bed and he is equally desperate to escape their clutches. The implication is clear: no woman of a certain age can be sexually desirable, any more than an old man.

Plato, writing in the first quarter of the 4th century, gives us an interesting portrayal of old age in the first book of his most famous dialogue The Republic. The setting is the house of Cephalus, an elderly Sicilian resident of the Piraeus who has grown rich from trade and manufacture. Athenian citizens mainly made their living from land, and it was men like Cephalus, “resident aliens” living in Athens and its surrounds without citizen rights, who controlled commercial forms of moneymaking. Plato’s Socrates has contempt for the life dedicated to money and for the complacency it can engender. At first we are lulled into sympathising with this picture of a dignified old man sitting in his household enjoying a peaceful old age free from cares. But the Republic was written much later than the time it portrays and Plato’s audience knew that Cephalus’ family had been ruined as a result of the war. The security based on wealth which the old man had spent his life building up was entirely illusory. As always, there is a malicious undertone to Socrates’ polite questioning. Before long, it appears that for the old man, morality is something entirely external, a matter of rules to follow and duties to perform. He doesn’t really care about morality and as soon as Socrates asks questions that require him to think, Cephalus loses interest and excuses himself. He has the ordinary person’s view of justice, and behind the comfortable affability we are shown a complacent and limited man.

But he is not entirely a bad example of old age. He tells Socrates that old men grumble about missing out on the pleasures of their youth but he thinks they’re missing the point. Some old men, he admits, no longer receive respect from their families, but this is the fault not of their old age, but of their character. If men are sensible and good-tempered, old age is easy enough to bear; if they are not, youth as well as age is a burden.

A century later, the Athenians were still enjoying performances of comedy, but the genre had undergone a change. Instead of dealing with public issues, comedy was more concerned with down-to-earth human affairs. Language was plain and typical of ordinary conversation. The master of this genre of New Comedy, as it is called, was the Athenian Menander, the creator of drawing-room comedy or the comedy of manners. The sands of Egypt recently yielded one of his lost plays that has as its central character a bad-tempered old man. Fed up with having to make decisions, he says to his son:

I’d like to speak briefly about myself and my ways. In a world where everyone was like me there wouldn’t be any lawcourts, or imprisonment, or war. Each man would have a sufficient amount and be satisfied. But I guess the status quo suits people better. Carry on then, this cantankerous old malcontent will soon not be here anymore to cause you trouble.

He is still master of the house and its property, but he wants no more of it. He just wants to be left to live as he likes. He is more humane than he pretends but doesn’t much like what he sees of the modern world. Here, if anywhere, we see why Julius Caesar said Menander held up a mirror to the world and its ways.

We can end on a positive note. Brought to trial by his son Iophon for allegedly being too senile to administer his will fairly, the dramatist Sophocles read out a speech from his last play and was immediately acquitted. He was 90 years old at the time. According to the character we have already met in Plato’s Republic, the same man, asked if he could still make love to a woman now that he was old, replied: ‘Stay off that subject; I’m glad to have left it behind me and got clear of a fierce madman in charge of my life.’