Golden Apples of the Sun

Joshua Barley considers past successes and failures in rendering Greek folk songs in English while working on a translation of his own

(© Dione Sarantinou)

(© Dione Sarantinou)

For those of us lucky enough to have been oppressed merely by tedium during lockdown, the onus was on finding things to do that were anything but tedious. And the book of translations I have been working on over the past two years has put a fire in my head.

When the first confinement began, I occupied myself by delving into a collection of books that had been amassing, largely unread, on my shelves over the last decade or so that I have lived in Athens. There is a kind of book that always catches my eye in Greek bookshops – a kind that seems both learned and beautiful; a hefty tome with lovely paper and a pretty cover; an excuse for the publisher to touch both the pride and nostalgia of their readers. The books I am referring to are of the so-called Dimotika Tragoudia, the Greek folk songs.

I was aware of the reverence reserved for these works, and had traced their influence in poets I had translated before (particularly the contemporary poet Michalis Ganas), but had never found the time or will to tackle this great body of work as a whole. Perhaps it was their presence in the schoolroom that put me off – to some Greeks they are indelibly attached to the pomp of national parades or to the libraries of fusty academics. Any such reservations, it turned out, were entirely unfounded.

‘Folk song’ is a fluffy, catch-all term – it might conjure up Victorian beards or hippy beards or evenings by the campfire; the songs might be scorned by literary types as pretty, ultimately insubstantial ditties. Yet if you consider that the works of Homer are, by some reckonings, also Greek folk songs, any such preconceptions swiftly disappear. Like Homeric epic, the modern Greek folk songs are the products of a long oral tradition. But it is a different one from Homer’s, one that developed in post-classical times and is still precariously alive.

These songs were not composed by bards but by ‘ordinary people’ of the villages (mainly women) in all corners of the Greek world, from Crete to southern Italy to Epirus to the Pontus to Cappadocia and to Cyprus. Rather than works of epic, they are short, finely-chiselled jewels, shining with drama, glittering with high lyricism. Their language is alive and extraordinarily innovative. And their subject matter opens a window onto the traditional world of the Greek villages, and all the wisdom and lore that was kept within it.

Even to put them all in the same ‘folk song’ bracket is somewhat misleading, and their original singers would not have considered them as such. They range from songs of historical events (such as the Sack of Constantinople in 1453), to songs of brigands (klefts), to ballads (longish narrative poems, usually with some element of magic, almost always with a grisly end), to love songs, songs of being ‘far from home’ (xenitias) and ritual laments. The latter are the most exquisite and fascinating, for enclosed within them lies all the mythology of death in the Greek tradition. You find depictions of Hades that seem to have changed little from ancient times (a vast, empty, ill-lit, un-watered space, the very opposite of a Christian Heaven); you find ‘Charos’ (the modern Greek personification of Death, descendent of Charon, ferryboatman of the Styx) in all sorts of guises – as pirate, invader, knight, or pied-piper of the mountains.

‘Why are the mountains black and welling up with tears? / Is it the wind that batters them, is it the rain that beats them? / It’s not the wind that batters them, it’s not the rain that beats them, / it’s only Charos passing by, with the dead-departed,’ begins one of Charos’ most famous songs, using the formulaic rhetorical device of question-and-answer – one of the marks of the oral tradition. The song goes on to depict this Greek Grim Reaper leading the young and old alike in his ghastly train (the ‘tender little children all arrayed upon his saddle’), stubbornly refusing to take his charges back to their home village, where they long to go. In these macabre songs of death, as in many of the other songs, a long-worked-out philosophy goes hand-in-hand with stark imagery.

Detached from their original music (as they inevitably are when in a book), the songs stand alone as some of the finest poetry in the Greek tradition. It seemed unthinkable to me that while a new translation of Homer is published every year in English, this treasure trove of the modern Greek tradition was inaccessible to an English-speaking reader.

By the time the orchids were out on the Hill of the Muses beside my flat, I had read most of the books of folk songs in my possession. By the time the hoopoes arrived I had persuaded my favourite Athenian publisher to make a book of the songs in Greek and English (if you don’t know Aiora Press, look them up – https://aiorabooks.com/ – their ‘Modern Greek Classics’ series has become the first port of call for anyone interested in the country’s literature). Timing favoured our plan – 2021 was the 200th anniversary of the Greek Revolution. ‘If we don’t publish them this year, we never will!’ pronounced Aris Laskaratos, Aiora’s energetic, charismatic founder. We didn’t publish them in 2021 (publication is due by summer 2022), but then again, the Revolution wasn’t won in a year either.

The coincidence with the anniversary of the Revolution was not merely an opportunistic move. For the collecting of the Greek folk songs is inextricably entwined with the move for Greek independence and the founding of the modern Greek nation. Initial interest in folk material was tied to the movement of Romantic Nationalism that took hold across Europe in the late 18th and early 19th century. In the same way that, say, the Brothers Grimm collected folk tales to provide a body of truly ‘German’ literature for the German nation, Greeks and Philhellenes sought a similar body of folk literature for the would-be independent nation of modern Greece.

The first published collection of modern Greek folk songs was compiled by a French Philhellene, the extraordinary polyglot and polymath Claude Charles Fauriel. Formerly private secretary to Napoleon’s Minister of Police, Fauriel would go on to become the Sorbonne’s first professor of comparative literature. He collected Greek folk songs from Greek intellectuals in Paris and expatriate Greeks in Trieste. The result, Chansons Populaires de la Grèce moderne, was published in 1824, the year that Byron died at Mesolonghi, and instantly shot around Europe, inspiring classicists and politicians towards the cause of Greek independence. The point, in a nutshell, was that if the Greeks can (still) compose such heroic verse and fight such heroic battles, surely they deserve their own nation. The folk songs were therefore seen as key evidence of cultural continuation with ancient Greece – the raison d'être of the modern Greek nation.

Fauriel’s collection was immediately translated into English by Charles Brinsley Sheridan, son of Sheridan the playwright. The Songs of Greece, published in 1825, was commissioned by the ‘London Greek Committee’, a group of thinkers, politicians and poets (including Lord Byron and Jeremy Bentham), founded to promote Greek independence from the Ottomans. Sheridan’s work was the first translation into English of the Greek folk songs, but it is only of historical interest now. He translated directly from the French, and even then was hardly faithful to Fauriel’s versions. Sheridan’s spirited verses, in the style of Walter Scott, bear little resemblance to the Greek, and are motivated principally by his support for the Greek cause, hamming up the Brave Greeks vs Nasty Turks opposition in a way that didn’t really exist in the original songs. It is an exercise in how a ‘translation’ can be manipulated towards the (political) goals of the translator.

It worked, of course – five years later Greece had its own independent, sovereign state. And while it would be a stretch to attribute too much influence to Sheridan’s book, there is no doubt that it played its part in stirring feeling towards the Greeks at a time when their Revolution was at an ebb and foreign support was needed most.

Within Greece itself, the same idea of cultural inheritance from ancient Greece was crucial to the national appropriation of the songs. Beginning in the early years of the modern nation, scholars attempted (with varying degrees of success) to find traces of ancient Greek culture that survived to modern times through the folk songs. A famous example is found in one of the ballads (an early version of my translation can be found here: https://www.periclesatplay.com/the-return-of-the-long-lost-husband), which has a ‘recognition scene’ of a long-lost husband by his wife that mirrors Penelope’s recognition of Odysseus with tantalising closeness. The nature of the link with Homer has been debated ever since.

Beyond national ideology, the songs played their role in the early literature of the modern nation. The first poets of modern Greece, notably Dionysius Solomos (Greece’s ‘national poet’, whose words are used in the national anthem), relied on the folk songs for the form and style of their poetry. Most major modern Greek poets (including Cavafy, Seferis, Elytis and Ritsos) have also drawn on the tradition. Moreover, the language of the folk songs was the foundation of what became known as the ‘demotic’ Greek language, which would ultimately become Greece’s official language. Their lines are in the very blood of anyone who speaks the language.

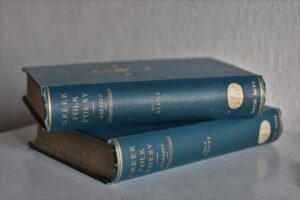

The second (and last) major translation into English of the folk songs was undertaken in the late 19th century by the English folklorist and traveller Lucy Garnett. Greek Folk Poesy, published in 1896 with introductory essays by John Stuart-Glennie, is a different beast altogether from Sheridan’s. Roughly synchronous with James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, this book was a contribution to the study of comparative mythology, at a time when grand-minded scholars were attempting (with bizarre and occasionally dangerous results) to answer dizzyingly enormous questions on the origins of religion and even the whole of human civilisation. Folk songs such as those translated by Lucy Garnett were read principally for the myths enclosed within them and as evidence of ‘primitive’ thought. As such, the book’s focus is not on songs of Greek war heroes, but on those that contain traces of universal mythology and arcane rituals. There is almost no crossover with Sheridan’s work.

Garnett, unlike Sheridan, knew modern Greek very well and her English translations are meticulously composed in exactly the same metre as the Greek (the 15-syllable line). This technical feat comes at the expense of the poetic quality of the English, which has to be padded out to fit the long line. Her translations received sharp criticism from none other than the young W. B. Yeats, who reviewed the book. ‘There can be no justification of the writing of verse except the power to write as a poet writes,’ he pontificates (a line to make any verse translator shudder), before going on to state, in no uncertain terms, that Lucy Garnett does not write as a poet writes.

For all of Yeats’s vitriol against Garnett, he elsewhere admits that a Greek folk song was the inspiration behind his sublime The Song of Wandering Aengus. The Greek source was undoubtedly from Garnett’s translations, and probably ‘The Fruit of the Apple Tree’, which ends ‘Come, gather youth! Come, gather them, the apples of my fruit tree; /And gather them again, again, and stoop again and again!’ It is quite easy to see the grounds of Yeats’s complaint against Garnett’s laboured verse. But there can be no greater justification for translating poetry than its power to inspire. I hope these forthcoming translations will be read by many, or by a few who might be inspired by them, by those who want to hear the voices of a lost Greece, or simply by those romantic, wandering souls, plucking till time and times are done, the silver apples of the moon, the golden apples of the sun.

Charos and the Shades, translated by Joshua Barley

Why are the mountains black and welling up with tears?

Is it the wind that batters them, is it the rain that beats them?

It’s not the wind that batters them, it’s not the rain that beats them,

it’s only Charos passing by, with the dead-departed.

He drags the young men in the front, the old men at the rear,

the tender little children all arrayed upon his saddle.

The old men are beseeching him, the young men on their knees,

‘Charos, stop at our village, do – stop at the clear fountain,

and let the elders have a drink, the fine young men play pebbles,

and all the little children go and gather flowers.’

‘I won’t stop at your village, no, nor at the clear fountain,

for mothers come for water there and recognise their children,

and husbands see their wives there too and won’t be separated.’