The PM Who Couldn’t Stop

Michael Llewellyn-Smith on writing the life of the colourful and tireless Greek prime minister Eleftherios Venizelos

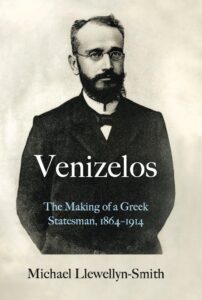

(© Cover by Rob Pinney for Hurst & Co, photograph probably by Pericles Diamantopoulos © Literary Society "Chrysostomos')

My book about Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936), Greek prime minister and (to say the least) controversial personality, was published earlier this year. The first of two volumes, it covers Venizelos’s childhood, youth and apprenticeship in politics, and his early steps in office in both Crete and Athens – the 'making of a Greek statesman', in the words of the book’s title.

The word 'statesman' is loaded. What does one have to do to deserve the term? One qualification may be to last a long time, but surely something more than this is needed. In Venizelos's case the justification lies partly in his role in forging – with his Serbian and Bulgarian colleagues – the Balkan alliance that pushed the Ottoman armies out of Europe in 1912-13, almost as far as the gates of Constantinople. What followed in the schism of the Great War years and their aftermath may lead some readers to question his statesmanship. But above all the justification lies in the far-reaching effect he had on virtually all aspects of Greek life, social as well as political.

Eleftherios Venizelos was born in a village near Chania, in Ottoman Crete, and was influenced by the rich mixture of Greek Orthodox and Muslims on the island. The Union of Crete with Greece did not come about until 1913, and he played a significant role in achieving it. His father Kyriakos, who had taken part in the Greek struggle for independence, sent Eleftherios to secondary school in Athens, and later to the Cycladic island of Syros, where he absorbed the history and ambitions of the young Greek state. But his father saw the boy's future as lying in the china and glass business he had established in Chania.

An enlightened Greek consul urged Kyriakos to send the promising youth to Athens University, which in the 1880s was a melting pot for students from all over the Greek world. In Athens, the young Venizelos absorbed the growing Greek nationalism that guided his political development. Back in Crete, this period culminated in his dispute with Prince George of Greece, the governor of Crete as High Commissioner of the Great Powers, over the tactics for achieving the Union of Crete with the mother country. The episode, including a staged revolution at Therisso in the White Mountains of Crete, did much to make Venizelos's reputation in Greece, initially as a troublemaker. He was widely and wrongly assumed to be a republican. In any case he was a man to watch.

His Cretan years were turbulent ones. (I quote Saki's satirical story The Jesting of Arlington Stringham: 'The people of Crete unfortunately make more history than they can consume locally.') Having wooed a Cretan girl, Maria Katelouzou, who became his first wife, Venizelos had to leave Crete for Athens in 1889 to escape possible arrest by the Ottoman authorities. A series of intensely passionate letters survives between the young man and his bride. They had been married for only a few years when Maria died of puerperal fever in childbirth delivering their son Sophocles, who much later was himself to become prime minister of Greece. Venizelos swore that he would never marry again. You can probably guess whether or not he kept that promise!

It was principally political developments in Greece which prompted Venizelos's move from Crete to the political stage of Athens. Following a badly thought-out uprising in August 1909 by a group of junior officers and NCOs, who made a mess of overseeing government by the 'old' politicians, Venizelos was invited to come over and find a political solution. He succeeded so well that within a year he was prime minister of Greece.

There followed five great years of creation. Backed by a large majority in parliament, he was able to revise the constitution, improve the finances, make a start at social legislation and help forge the alliance of Balkan states that pushed the Ottoman armies back to the threshold of Constantinople. In these years Greece became a country taken seriously by the Powers of Europe, and Venizelos the politician started to be seen as a leader of European dimensions. But fate had nasty tricks up her sleeve. The turbulence unleashed by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand soon interrupted Venizelos's reform programme. The problems of war and peace he now faced were existential for the small countries of Europe, Greece included.

In 1914 Venizelos was fifty years old and had more than two decades still to live. These years were full of drama for his country and people and for himself. In some ways they are more interesting than his early life, because the politics are played out on a wider playing field, against a background first of the European war in which Greece was willy-nilly involved, and second of the risky invasion of Asia Minor. In other ways they are more difficult to describe owing to Venizelos's fallow periods – though these were adorned by his translation of Thucydides into a moderate purist (katharevousa) version of modern Greek.

The disaster of the Great War generated a breakdown in political life and standards of behaviour known as the National Schism, which poisoned Greek politics in the interwar years and even beyond. The country was divided physically and morally. After the war the Greek occupation of Smyrna (Izmir) and the Greek-Turkish war that followed led to what Greeks call the Asia Minor catastrophe: the defeat of the Greek army by Mustafa Kemal's Turkish nationalist forces, the burning of Smyrna and the forced migration to Greece of some 1.5 million Greek Christians from Asia Minor.

Greece was reconfigured by the great migration of Greek Christians from Asia Minor. Venizelos himself returned to power as prime minister in the late 1920s, to the applause of his faithful supporters and the contempt of his opponents. His comeback was one more episode in the hopeful starts and shifts and juddering stops of his career. He died in 1936, in exile in Paris, and is buried in Crete, in the hills above Chania (how he got there is a story in itself).

Venizelos was always threatening to abandon politics, but he always came back. Perhaps he should have resisted the temptation to do so. Venizelos's later career, which I am currently writing about for the second and final volume of my Venizelos biography, comes close to illustrating the harsh axiom of Enoch Powell: 'All political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs.' That is too harsh, surely, as well as being untrue, though one can see what Powell was getting at. As for Venizelos, there were happy junctures where he might have stepped down and stayed down. But he could never bring himself to stop.