Professor Sir John Boardman (1927–2024)

Paul Cartledge fondly remembers his friend and graduate supervisor at Oxford, a giant in the international study of classical art, and a much-admired man besides

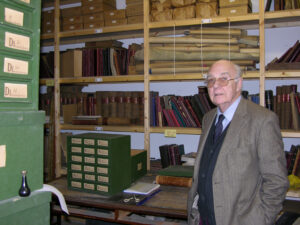

John Boardman inspecting gems at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire (© Claudia Wagner)

John Boardman inspecting gems at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire (© Claudia Wagner)

Professor Sir John Boardman has been ferried peacefully across the Styx at the ripe age of 96. He was a true makrobios, usefully active both intellectually and physically almost to the very end of his long, adventure-filled and massively productive academic and personal life.

He was born in Ilford to a non-academic family, educated privately at Chigwell School near Epping Forest (he had vivid teenage memories of aerial bombardment in the Second World War) and studied for his first-class degree in Classics immediately postwar at Magdalene College, Cambridge. At university he combined the heartiness of rowing with a prodigious and enviable ability to learn by heart and recite before the college Master the First Olynthiac Oration of Demosthenes – in the original Attic Greek.

He wrote or co-wrote and edited or co-edited well over 30 books in the course of some six decades. There were handbooks (on Attic black- and red-figure vases, Archaic [i.e. pre-Classical] and Classical Greek sculpture); a lecture-collection (the 1993 Andrew W. Mellon Lectures in Fine Art, D.C., published as The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity and awarded the Runciman Prize) and a longform essay (Preclassical); heavy-duty academic monographs (most notably Greek Gems and Finger Rings, Persia and the West and The Archaeology of Nostalgia, another Runciman winner); numerous catalogues (including many on gem collections, Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum and more recently one for the Mougins Musée d’Art Classique); and excavation reports (Chios 1967, Tocra in Libya 1966–73). The 1970s was an especially abundant and fertile decade.

Boardman also published numerous journal articles, including generous appreciations of colleagues. Not the least of his qualities was that he was not the sort of academic to indulge in backbiting or point-scoring of a negatively personal kind. He supervised vast numbers of graduate students, scattered over several continents, who repaid his care for them with fervent devotion. For an academic to receive even one Festschrift is usually considered accolade enough, but Boardman received several, the most recent published in Portugal to mark his 90th birthday.

He had an extraordinarily acute and retentive visual memory and was highly efficient and well organised both in his teaching (his lectures on Greek architecture and sculpture were a revelation) and in his research and writing. No luddite, he welcomed the new technology of digitisation with gusto. There can be few students of ancient Greece – from the Mycenaean Late Bronze Age down to its later Roman imperial manifestations – and of its cultural diffusion and reception beyond the Mediterranean who have not encountered his contributions.

John Boardman once wrote that he felt more at home intellectually outside Oxford, indeed outside Britain. For his huge attainments and contributions, he was amply rewarded and recognised by a dozen academic bodies and institutions: in Ireland, in continental Europe (Greece, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Russia), and further afield (United States, Australia). He was duly honoured, too, with many prizes and other kinds of distinction: honorary Fellowships of his three Oxbridge colleges (the Oxonian being Merton and Lincoln), a knighthood, the Kenyon Medal of the British Academy, and the Onassis Prize for Humanities (bestowed ‘sous la coupole’ at L’Institut of the Académie Française) among them.

In the early 1950s, following National Service in the Intelligence Corps, he served for three years as Assistant Director of the British School at Athens. For almost 30 years he was on the board of the Basel-based Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. But he by no means neglected the UK. He edited the Journal of Hellenic Studies for seven years, and for a decade was a Delegate of Oxford University Press. He occupied what had originally been Edward Gibbon’s seat of Professor of Ancient History at the Royal Academy.

He was not shy of entering publicly into serious academic controversies, the dating of Arthur Evans’s Knossos Linear B tablets, and the colour of ancient silver, among them. His incisive, considered contributions always illuminated and often resolved debates. But he was resolutely apolitical, with the one exception, perhaps, of his view that Elgin’s dubiously acquired collection purchased by the UK in 1816 should remain in its entirety under the curation of the British Museum trustees. His very last book publication, produced by Thames & Hudson, was a lightly-illustrated repackaging of his lively 1985 text composed to accompany the photographs of David Finn in their The Parthenon and its Sculptures.

Boardman seems to have had a thing for Greek islands: Euboea (modern Evvia), Chios and Crete, above all others. Eschewing a not yet fashionable or necessary doctorate, plain Mr Boardman uncovered in the depths of the Athens National Museum (while Greece was riven by a vicious civil war) a diagnostic Euboean pot-shape that enabled archaeologists since then to track the path of Greeks and Greek culture both East (Al Mina in Syria) and West (Pithecusae, today’s Ischia) and at many points between, thanks to which we westerners owe among much else the diffusion if not invention of our alphabet.

Greeks overseas, including dead Greeks overseas, were to be a special preoccupation from the mid-1960s to the late 1990s. The fourth edition of his 1964 Pelican Greeks Overseas was published, with a new subtitle (Their Early Colonies and Trade), by the house with which so many of his foundational works were associated, Walther Neurath’s Thames & Hudson. On Chios as a handsome young man, he joined a celebrity-studded cast of foreign excavators and helpers including Dilys Powell (widow of Humfry Payne) and Michael Ventris, the architect who that same year announced his decipherment of the Linear B syllabic script as an early form of the Greek language. In 1961 he published on the Cretan collection of the Ashmolean Museum where he was curator.

It was working on another, private collection of art-objects in the 1990s that gave him ideas about world art, its interconnections and aims. This led him to distinguish three main ‘belts’: a northern one running from Siberia to North America, an urban one from China to central America, and a tropical one to the south (World of Art, 2006).

Boardman adored Greek gems and finger-rings. With the indispensable aid of photographer Bob Wilkins and later Claudia Wagner, a senior researcher at Oxford’s Beazley Archive, he stamped his seal on a field of ‘minor’ art that he showed could be anything but. The title of Masters in Miniature, co-authored with Wagner, hits the nail on the head. Part III of his challengingly subtitled 2020 autobiography, A Classical Archaeologist’s Life: The Story so Far, reads simply, ‘Gems, Bob and Claudia’. That retrospective, end-of-life work reveals also just what an inveterate globe-trotter he had always been, at first with his artist wife Sheila (née Stanford) and their young children, Julia and Mark, and later mostly with Julia.

Late in life, John Boardman had some trouble with his eyes, but his mental, intellectual and art-historical eye remained resolutely clear. Such a cursus honorum as his, possibly not to be equalled in the future, is a beacon of light amid Classical studies’ present darknesses. The intellectual community of art historians, as well as historians of ancient Graeco-Roman civilisation and culture, has lost one of its most consistently and penetratingly, even bracingly brilliant interpreters and foremost communicators.